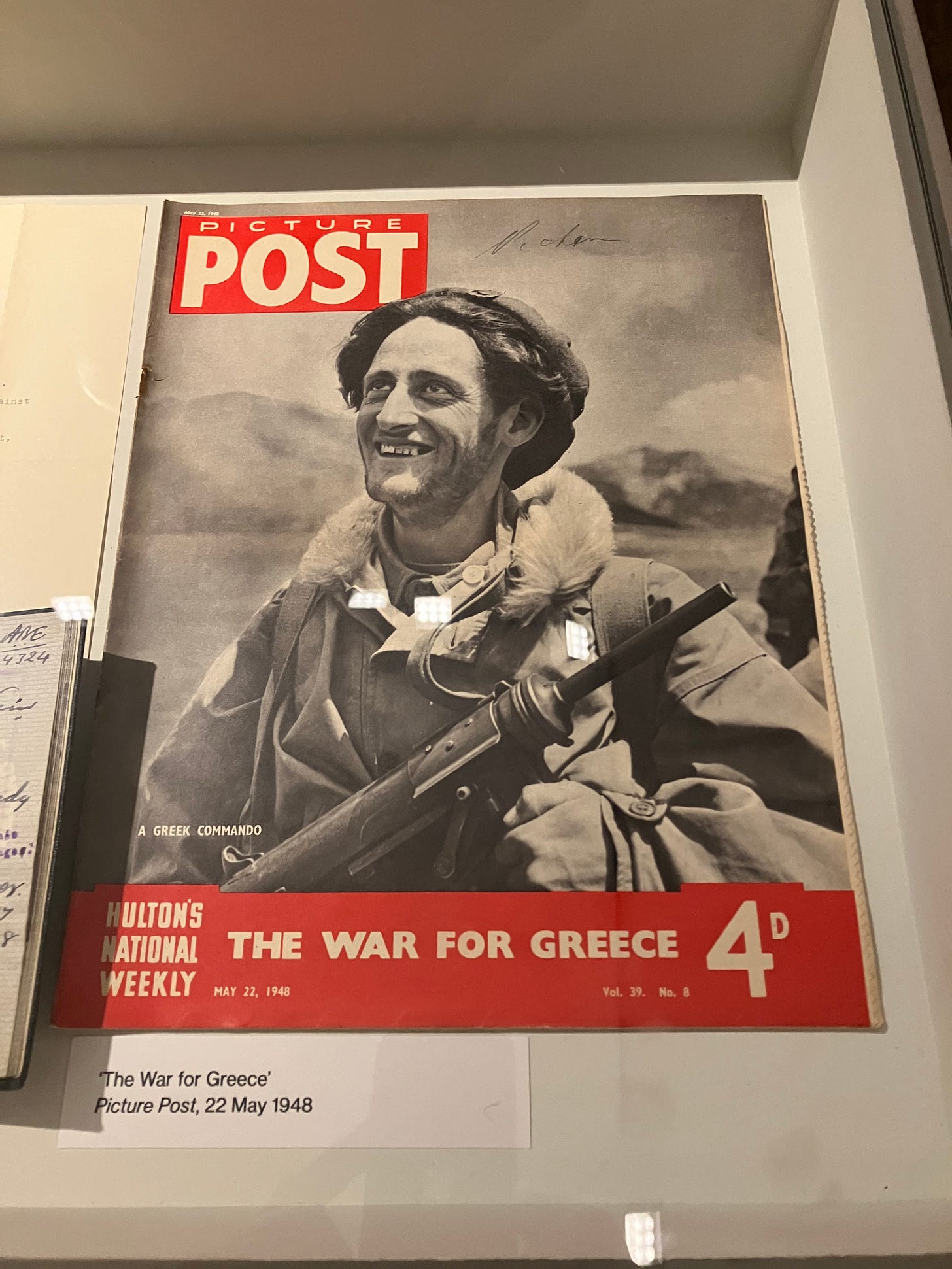

Looking recently at some photographs taken after the Second World War in Greece by Bert Hardy currently on show at The Photographers Gallery in London I found myself recalling a small café in Athens in the Plaka district, where, several years ago, I was sipping from a tiny white cup of coffee. I looked up and saw that the painted wooden sign above the heads of the two old gentlemen opposite me read ‘The Old Man of the Morea’, the name given to the colourful general of the Greek War of Independence, Theodoros Kolokotronis. Shortly before leaving on that trip I had read Nikos Kazantzakis’ account of his Travels in Greece, written originally as a set of newspaper articles in the 1930s and in his chapter on Kolokotronis the author of Zorba the Greek describes the 19th Century warrior’s life as “a dramatic, characteristic unfolding of a rich modern Greek soul: faith, optimism, tenacity, valour, a certain, practical mind, deceptive versatility, like Odysseus”, a very characteristic Kazantzakis sentence!

The two men smiled benignly and asked me first where I was from and then what I did for a living. Years ago I learned the Greek word for writer: syngrapheas, [συγγραφέας] and so was able to answer their question in Greek. They nodded approvingly and asked what kind of books I wrote: “Histories?” Realising that my command of modern Greek was already reaching its outer limits I nodded. It seemed the easiest way of answering their question. But even when I am at home, speaking in English, this is a question I find myself responding to uncertainly, even shiftily, never sure quite what to say. As writers we are often the prisoner of the terms of genre, a kind of pigeon-holing that we kick against, yet I have even kicked against the broad term itself: writer.

30 years after my first book was published I am still not sure what to call myself. Before that first book, published when I was just 40, I used to call myself by another word: journalist – in Greek dimosiografos [δημοσιογράφος] which I suppose you could translate literally as ‘public writer’. I seemed reasonably happy with this. It described what I did for a living. I was a member of the National Union of Journalists. I wrote articles for unglamorous trade magazines. My literary persona was still waiting to emerge fully with that first book which was followed by such a breathless race to catch up that today, if I swell the bibliography with all those little pamphlets, I have notched up 29 International Standard Book Numbers. I think I am entitled to call myself a writer so why the hesitation? Why the faltering tone?

I suppose I have to say that while always wanting to write I never recall saying: ‘I want to be a writer’. Did I think it pretentious? Presumptuous? I am not sure I can put my finger on it exactly but, somehow, I want to decline the status of writer. I want to shift attention to my books, my words, the tangible products of the writer’s craft. I say this in the face of what sometimes feel like intolerable pressures on writers now to be writers, to play the part, to strut on the literary stage, to sell themselves as much as their books. But I realise that I cannot say this is new. When I was writing my biography of Aldous Huxley I turned up in my research many magazine profiles of the 1920s and 1930s for which the writer had to make himself available, often playing up to it – foppish, epigrammatic, an angular, Old Etonian Oscar Wilde. In the 19th Century Dickens, Trollope, and, yes, Oscar Wilde went on extravagant tours of America flaunting themselves as writers, personalities, phenomena. I have always cherished that acid put-down by the literary critic F.R. Leavis of the Sitwells: ‘they belong to the history of publicity not poetry’. The Sitwells would have been unfazed.

But it is a little late now to complain of this. Writers’ contracts with publishers increasingly state that the author must be available for publicity tours, bookshop signings, festival appearances, and other promotional activity. Many writers enjoy these events, making contact with readers as real people rather than abstractions, getting out of the isolation of their writing-rooms. Writers like J.D. Salinger who were recluses are very rare these days though when I saw Don de Lillo on stage at the Hay Festival some years ago I thought he looked uncomfortable. Not normally given to these sorts of exposure he responded courteously to Jim Naughtie’s resourceful questioning but made me feel that this was not a happy excursion for him and one that served little purpose either for him or for us, his readers. I experienced something similar last week at the Irish Embassy in London where Paul Lynch, “Booker Prize-winning author” of Prophet Song was on show. Fluent – perhaps a little too fluent – in his answers to the Guardian journalist interviewing him on stage, I felt that Lynch didn’t need this performance, playing The Writer, saying too much, when it was the work itself that should have been sufficient.

Coming back to those old men of the Plaka, my difficulty was not, however, a fear of exposure, of self-advertisement, it was rather a difficulty about definition, about which pigeon-hole to place myself in. I have written in many genres: poetry, fiction, travel, biography, essay, political polemic, autobiography, topography, cultural criticism. Often I have written in combinations of these, mixing travel and personal reminiscence, for example, or politics and poetry, or fiction and autobiography. I like writing which promiscuously plays with multiple genres. I like digression, going off at a tangent, mixing it. The problem with literary genres and classifications, so popular with librarians and booksellers, is that they can be limiting, forcing us into moulds, down narrow alleyways we don’t really want to venture into.

One of my early books was called A Short Book About Love. A plain enough title, you might think, but what exactly was it? “It’s not a novel,” was the reported comment from my mother’s neighbour. Was this intended as a criticism? I didn’t take it as such. It certainly contained fictional elements, some properly fictive in the sense of being purely invented, others lightly disguised autobiography. Some passages, reflecting on the various kinds of love, were more like essays, even literary criticism, and binding this all together was a re-telling, in a generally light-hearted style, of the medieval legend of Tristan and Iseut. It didn’t stop there for, threaded into this variegated texture, was my attempt – indirect, exploratory, tentative – to say something about the recent death of my father which may have been the immediate trigger for writing the book, though not its declared subject. I am happy to say it wasn’t a novel in the conventional sense and, if pressed, I suppose I would settle for a ‘fiction’. But in truth I wasn’t perturbed by its failure to follow the expected rules of one or other genre. I just wanted people to pick it up, read it, and (if they could) enjoy the variety, the multi-faceted quality, the unexpectedness. Just as contemporary composers of classical music expect us to listen with open ears, without the presumption that their new work will necessarily sound like Haydn, wanting us to enjoy the new and possibly unexpected sounds that their musicians deliver, so I think a book should be granted the permission to speak on its own terms, to ask, politely, for a hearing, even if the accent is surprising or initially odd.

Wordsworth said that the poet must ‘create the taste by which he is understood’ which I take to be not an arrogant imposition of something alien to the reader, a deliberate flouting of expectation, but an invitation to try something different, to give it the benefit of the doubt, to let it work on you. There is no compulsion here. No one is obliged to read, listen to, look at, anything they genuinely don’t like but until one has tried something one will never know whether or not it could be to one’s taste.

In a more recent book, published in 2016, Crossings: a journey through borders, I explored the idea of borders, literal and metaphorical. It contained very straightforward accounts of border crossings around the world as well as reflections on the meaning of borders. It meditated on borders of class, culture, even the border between life and death. One reviewer described it as ‘a collection of essays’ on the theme which, if it would help the people who have the task of filing it in the right place, I can live with, though I perhaps saw it as a more integrated patterning, if not a seamless garment then one that seemed to be woven from the same material.

Some of the most successful and original contemporary authors, like the late W.G Sebald – or in a lighter vein Geoff Dyer – have produced books which one would struggle to assign to a definite, watertight category yet they are none the worse for that. The human mind is various, venturesome, playful, exploratory, curious, unpredictable, drawn to chance associations, unexpected connections as much as it is insistent on always getting what it thought it wanted to begin with. Creativity is just that: making it new and different, following the imagination’s spontaneous promptings, letting go.

Am I saying, therefore, that genre is a nuisance, an encumbrance, something we need to escape from? A straitjacket? I don’t think so. There are pleasures to be had from genre, from seeing its disciplines and skills at work. A well-constructed novel with a beginning, a middle and an end, a tightly-crafted play, a suspenseful thriller, an informative cradle-to-grave biography are all admirable and give pleasure. If there are no rules then there are no rules against rules and, working within certain formal constraints and expectations is itself pleasurable and satisfying for the reader as well as the writer. I have used the word pleasure twice in succession and this may be the key to my aesthetic of hedonism. Write what you want, read what you want, enjoy whatever comes your way, would be my permissive mantra. Don’t box yourself in, feel free to experience whatever you want to experience.

But there is more to the concept of genre than this. It should not be seen as a necessary constraint on creative freedom. The poet Robert Frost famously said that free verse was like playing tennis with the net down. T.S. Eliot, however, argued that the best free verse was always shadowed by the formal verse it seemed to be repudiating, that there was, in fact, no such thing as free verse, poetry being an art that demands its own exacting discipline, letting it all hang out not being the prescription for good poetry. I tend to agree and would add that formal constraints in poetry are not in any sense a curb on creativity. On the contrary, they can be an opportunity. Using regular forms or, to borrow a term used by the poet A.E. Stallings who writes almost exclusively in regular metres, ‘received forms’, involves responding to a creative challenge that can yield fine results. Testing oneself against the demands of form, trying to overcome what could look like constraints, can be a source of invention and creative excitement.

One of the great formal resources of poetry is rhyme. Often mistakenly thought to have gone out of fashion (except in hip-hop) it is in fact very much a living feature of contemporary poetry though not every poet uses it to the same extent or with the same frequency. It answers to a need to create formal patterns in verse. It is not just a matter of following some rigid rule of matching sounds, it is intimately involved in the structure of sense in a poem, the re-enforcement of meaning. Rhyme is found in various metrical forms that are still very much in use. A few years ago I published the third of a series of poetic satires written in very tight, regular prosodic forms. It was a pamphlet-length political satire called A Dog’s Brexit (Melos Press). As the title suggests it is a hard-hitting Swiftian satire on the political situation in the mad Brexit years but it uses a very strict form known in the poetic trade as ‘the standard habbie’. This derives from a famous 18th Century lament for a Scottish piper called Habbie Hamilton that first used this verse form but it was quickly taken up by Robert Burns and is sometimes known as ‘the Burns stanza’ or ‘the Scottish stanza’. First used in a serious elegy it became increasingly the vehicle of satire and was revived in the 1980s by poets such as John Fuller, James Fenton and Clive James. I used a slightly altered version of the Burns stanza as modified by W.H. Auden which essentially adds an extra line to the stanza and I have to say that, apparently very strenuous as it is in its formal demands, it is great fun to handle and, I hope, for the reader or listener great fun to hear. Rather than prolong this prosodic lecture let me offer you a short extract. All you need to know is that the speaker of the poem is a dog:-

1.

Who’d be a dog in England now?

They patronize my suffering brow

with soft caress.

Sometimes I snatch my bone and race

into some dark, secluded place

unable to remain at home and face

this rottenness.

Let me, a hound with drooping ears, dissent

from all that yapping rabblement

of loud MPs

so that a calmer, canine view prevails

above the shrill, discordant wails

of Members as each tries (and fails)

to please.

Which part of ‘exit’ did you miss?

constituency parties hiss

at those

too frightened to assert,

that cutting loose will hurt

more than it heals (as every Jacques and Kurt

well knows).

A noxious vapour reaches overseas,

borne on a toxic, xenophobic breeze

of hate.

And friends abroad, whose own Far Right

grows eager for a matching fight,

predict a European night.

Too late!

It would certainly have been possible to have written a poem on this theme that declined to make use of any formal properties, rhymes, received metrical forms, but I have a feeling that it would have been less entertaining. Political poetry always runs the risk of turning into a rant and although, actually, this is a bit of a rant, as you can plainly see, and I wanted it to be so, it can be enjoyed (and I have found this in the couple of performances I have given of it) even by listeners or readers who are less exercised than I am by its subject matter. I have made clear that for me the pleasure principle is central in any art form and if the formal resources of poetry, the demands and opportunities of this or that formal or generic discipline, give pleasure, add to the fun, then let us embrace them.

To return yet again to my two elderly Athenians in the shady café on the slopes of the Acropolis, what would I have told them had my Greek been up to the challenge? I think I would have said that we write, in the end, what we want to write, what works for us, what something deep inside ourselves seems to prompt us to write. This can involve gladly embracing the opportunities and stimulus provided by the rules of a particular genre or it can mean breaking free and experimenting. Or choosing any point along that spectrum. There are no rules for the novel, Aldous Huxley once said, it only has to be interesting and if one has written something interesting and the reader finds it interesting then what more could one wish for?

So I will tell them that I have written some books, very different from each other, and they must feel free to choose, adding that only one has actually been translated into Greek!

This is a revised version of a piece that originally appeared on the website of the Royal Literary Fund. In the coming weeks I intend, from time to time, to revisit some of those pieces, updating and expanding (or contracting!).

Let me say that this was an enjoyable and pleasurable piece of writing!