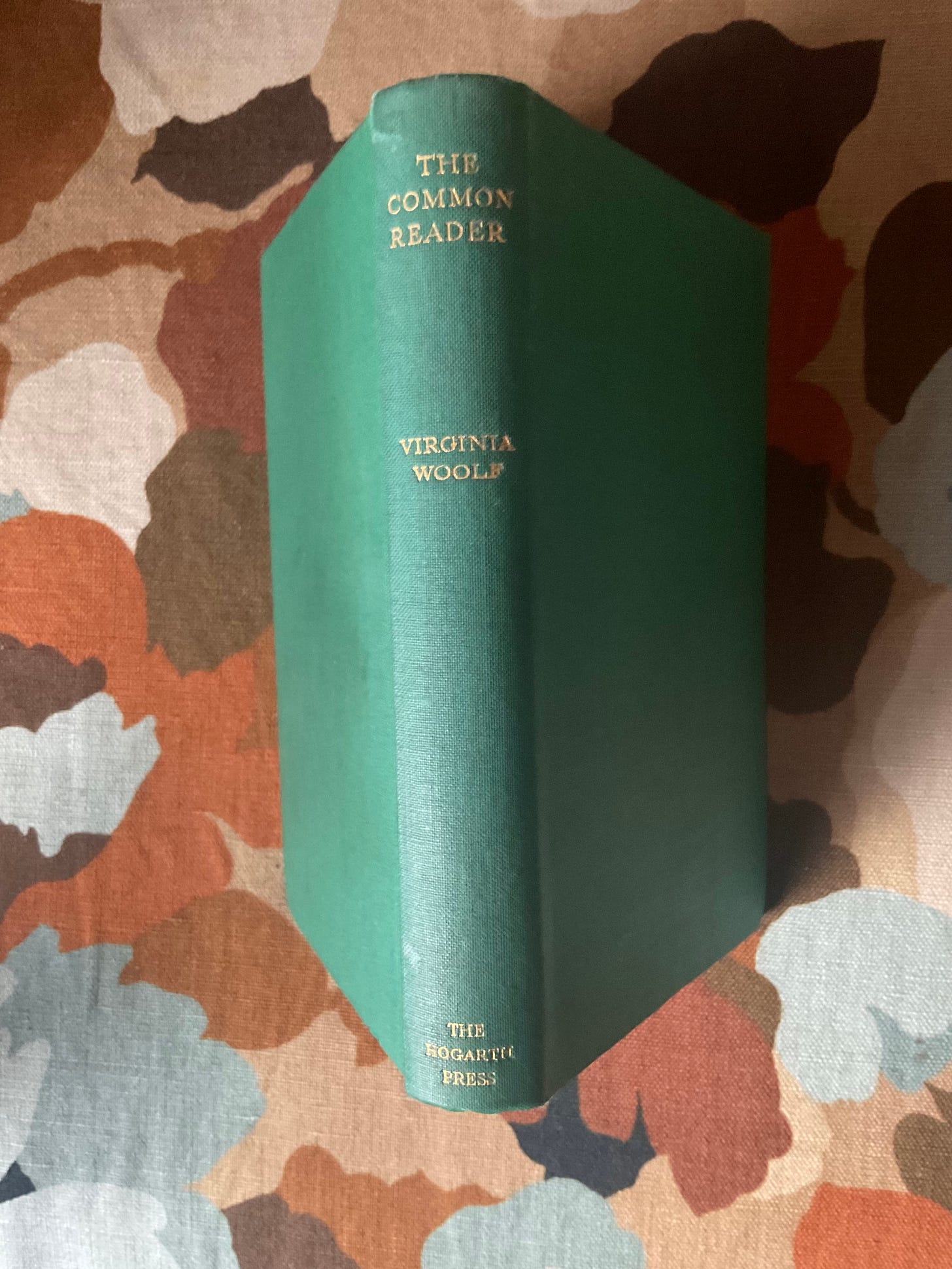

This year is the centenary of Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs Dalloway. Her first book of collected critical essays, The Common Reader was also published in 1925. In fact there are those who think she was a better critic and essayist than she was a novelist but let’s put that one aside and look briefly at The Common Reader. Woolf was neither common (as we all know) nor an ordinary reader. These essays are beautifully written and full of insight into writers like Defoe, Jane Austen, Chaucer, George Eliot and Joseph Conrad.

The Common Reader concludes with an essay “How It Strikes a Contemporary” which struck me as, well, very contemporary. She begins by pointing out that critics who are in perfect agreement about the status and value of literary works of the past are likely to come to blows when it is a question of a living writer. This is disconcerting, she suggests, “to the reader who wishes to take his bearings in the chaos of contemporary literature”. Is there no guidance, she asks, “for a reader who yields to none in reverence for the dead, but is tormented by the suspicion that reverence for the dead is vitally connected with understanding of the living ?” She alludes to a past where great critics like Dryden, Johnson, Coleridge and Arnold laid down the law confidently and to a present where there is no obvious high voice of critical authority. (Mr Eliot, Mrs Woolf?) “Reviewers we have but no critic; a million competent and incorruptible policemen but no judge.”

Woolf’s explanation is that great critics are “bred from the confusion of the age” and her age (c.1925) is “meagre”, “a lean age”, “an age of fragments” with no literary giants stalking the earth. “If we make a century our test, and ask how much of the work produced in these days in England will be in existence then, we shall have to answer not merely that we cannot agree upon the same book, but that we are more than doubtful whether such a book there is.” Well, we have now reached that centenary point and must ask : was she right? Looking back to the 1920s we can immediately suggest Ulysses (let’s not go into the complexities of her opinions on Joyce), The Waste Land, and, even keeping just to 1925, Suspense, St Mawr, Juno and the Paycock, A Draft of XVI Cantos, A Vision…I would argue that these titles are still very much “in existence”.

More interesting, perhaps, is what will be on such a list in 2125. Immediately one starts to understand her doubts but this is largely because we don’t have the leisure of that long perspective any more than she did. Is our contemporary literature “meagre”? As Chairman Mao said when asked if the French Revolution had been a success: “It’s too soon to say.”

But I would stick my neck out and agree that the state of criticism is not something to write home about – or that is how it strikes this contemporary. Poetry criticism in particular is in a very bad way, when it exists at all (for most serious books of poetry are lucky to get reviewed) and, reading for example the poetry review column in last Saturday’s Guardian not to be reviewed at all may not be such a bad thing. Partly as a result of the bad influence of online hype and encomia-inflation much poetry reviewing – even in the ‘quality’ papers – just now is a kind of breathless blurb-making. But is the alternative the hanging judge, the all-powerful arbiter, the Alvarez or Ian Hamilton? Isn’t a bit of diversity, plurality of taste a good thing? Certainly, we don’t want to be told what to read but I would appreciate more intelligent evaluation of contemporary poetry, more willingness to practise the art of criticism, more willingness to say something is not good if it is not good and to explain why one judges so, with conviction.

The last word goes to VW: “As for the critics whose task it is to pass judgement upon the books of the moment, whose work, let us admit, is difficult, dangerous, and often distasteful, let us ask them to be generous of encouragement, but sparing of those wreaths and coronets which are so apt to get awry, and fade, and make the wearers, in six months time, look a little ridiculous.”

I get your drift about things being too soon to say, but this was not something attributed to Mao, but a misunderstood comment by his Foreign Minster, see https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q-oro-ed4-00018657Mao

Shucks, I’ve often used this one, not knowing it was not a genuine quote. That said, I imagine a lot of Famous Quotes weren’t ever said by those alleged to have said them!